On the idyllic shores of southern Mozambique, three very special resorts provide access to an extraordinary marine environment—and the chance of a brighter future for the people who call the region home.

I watched the land closely from the air. The chocolate-brown earth of South Africa, bare and threaded with rivers that turned quicksilver in the morning sun, gave way to grassland in Mozambique. Perfectly round lagoons appeared, their barren circumference suggesting brackish water. That hint of salinity was a prelude to the sea, but no preparation for what came next.

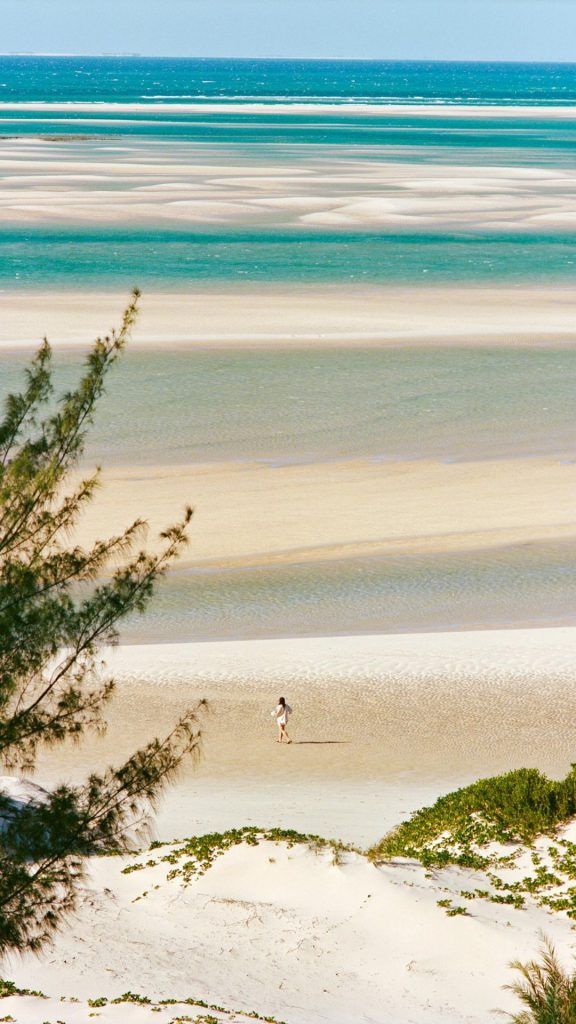

The plane tilted and the sun burst through the windows, sending ovals of solid gold over the cabin walls. I looked down at the islands of the Bazaruto Archipelago and the sea between them, a low tide streaming out in 20 tantalising shades of blue. The sprawling expanse of a sandbar had pushed through the shallows. My first thought was of a sculpture in sand, reminiscent of those works of early Cubism—Picasso’s Tête de Femme (Fernande), perhaps—in which all the facets of a face are seen at once, myriad planes collapsed into a single visage. The sea seemed almost to act like shadow, highlighting and deepening the lines of that piercing countenance.

“I simply think that water is the image of time,” wrote the poet Joseph Brodsky in Watermark, his meditation on Venice. My first glimpse of the Bazaruto Archipelago evoked that sense so many cultures have of the sea as a metaphor for divinity—now in the Spirit of God moving upon the face of the waters in Genesis, now in Vishnu floating on a cosmic sea. Water: it is the element that best represents that sensation of stillness, movement, and simultaneity that we know, in our heart of hearts, offers a glimpse of the divine.

The Bazaruto Archipelago is a chain of five islands in southern Mozambique, on the edge of the Indian Ocean. It is located at the junction of two wildlife “corridors,” which species such as humpback whales and blacktip and hammerhead sharks use to migrate up and down the eastern coast of Africa. The region also has many variable weather systems that give it an extraordinary diversity of habitats, from sand flats and mangrove swamps to freshwater lakes.

The archipelago is beautiful beyond conception, but it was not beauty alone that I found so affecting that morning. A feeling of fragility had come to me during the pandemic. I was emerging from months of isolation. My first attempt to visit in November of last year had failed: Omicron struck, and Mozambique was one of eight African countries hobbled by COVID-related travel restrictions.

The trip had to be cancelled, but naturally I got sick anyway, sitting in upstate New York. It had been a long, bitter winter that had made me almost fearful of travel. Dropping south from JFK on a 15-hour United flight to Johannesburg, sailing into the Southern Hemisphere, I found myself balancing the thrill of being out in the world again with a new sense of precariousness. The enthralling spectacle of the archipelago was edged with a degree of sadness. I was reminded of the fear that almost kept me from leaving home. If ever proof were needed of how wonderful the world is, there it was in that translucent expanse of sea and sand beneath me, the image of all that was ephemeral and enduring.

Mozambique sits like a slumped Y in the southeastern quadrant of Africa, its tail in South Africa, its horns facing north to Tanzania, Malawi, and Zimbabwe. The Zambezi River runs along its slender waist, separating a predominantly Muslim, Swahili-speaking north from a Bantu Christian south. A coastline of some 2,414 kilometres gazes out at the Indian Ocean, a geography that has, over the course of history, often made the south of the Arabian Peninsula and the western coast of India feel as much a part of Mozambique’s story as the continent of Africa is. It was the sea that brought Arab traders to these shores for a thousand years, beginning in the 10th century, and the sea that drew Vasco da Gama in 1498, on his way to India. His arrival marked the beginning of the Portuguese presence in Mozambique, which continued unevenly for nearly 500 years, driven by a greed for gold, ivory, and, as was so often the case in Africa, people to enslave.

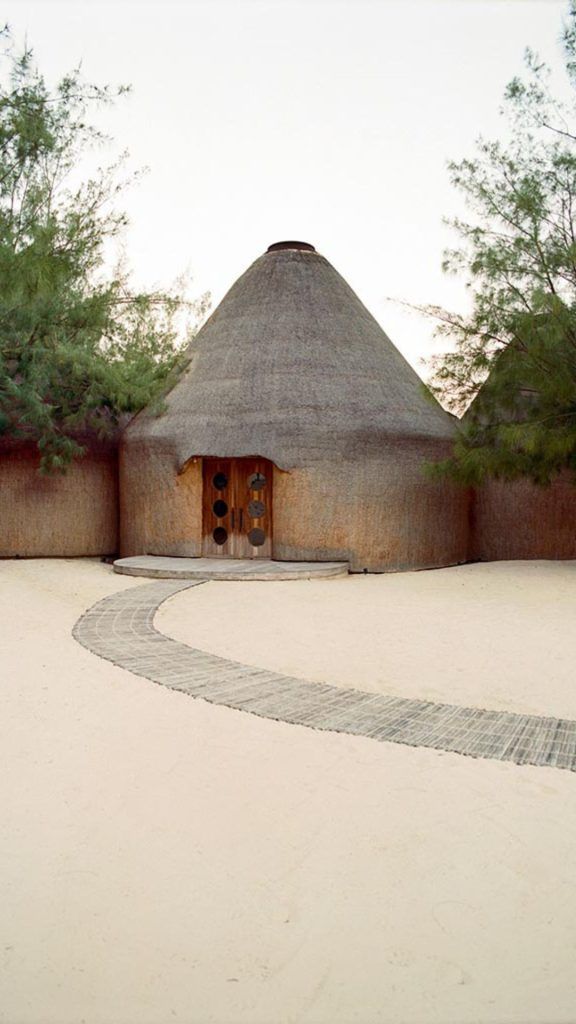

Vilankulo, a coastal town of some 25,000 people, is the gateway to the Bazaruto Archipelago. Once I had cleared the languors of immigration at its diminutive airport, I was met by Mario De Figueiredo, a bush pilot with a bright-red helicopter. Ferrying me between the mainland and Benguerra Island, De Figueiredo pointed out villages with circular houses made of local madjeka (thatch) and caniço (reed). I saw unpaved roads of sand among a rich, glossy vegetation of palms and fruit-laden trees, dunes, and clear-water lakes.

De Figueiredo grew up in the final years of Portuguese rule in Mozambique. It had taken the fall of dictator Antonio Salazar in 1968 for Portugal to finally begin to relinquish parts of Africa over which it retained a stubborn stranglehold, even as it kept them willfully underdeveloped. In less than a year, three nations won their independence—Guinea-Bissau in 1974 and Angola and Mozambique in 1975—the latter at the hands of a Marxist-led freedom movement called frelimo. Describing the precariousness of that moment in his 1992 book A Complicated War, the New Yorkerwriter William Finnegan wrote, “The illiteracy rate was over 90 per cent. There were fewer than a thousand Black high school graduates in all of Mozambique.”

De Figueiredo left the country in 1974, aged 14, and moved to Portugal as part of a mass exodus of Africans of European descent. Scarcely two years of peace ensued before the newly independent nation was plunged into a 15-year civil war. It is hard to exaggerate how utterly wretched that conflict was. A million died, and 4.5 million were internally displaced. This poorest of poor countries was pitted with land mines, and had a brutalised population of dislocados (dislocated peoples), mutilados (amputees), and bandidos armados (armed bandits).

Frelimo’s goal was to establish Africa’s first Black Marxist state in Mozambique. It was also what the scholar Sayaka Funada-Classen has described in The Origins of War in Mozambique as “the first serious defiance of colonial authority in southern Africa.” Neighbouring apartheid regimes were not about to countenance such a state on their borders, especially one that gave refuge to Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress. They viewed the new country as a mortal threat and, as a result, Mozambique was drawn into a hideous proxy war, becoming one of the last great theaters of the Cold War. China and the Soviet Union supported the government against an insurgency that was backed first by Southern Rhodesia and later, once that country became Zimbabwe in 1980, South Africa. It took the end of the Cold War and the demise of apartheid for this ravaged nation to know a modicum of peace.

That night at andBeyond Benguerra Island, the stars were upside down. The sky that James Joyce described as a “heaventree of humid nightblue fruit” revealed constellations—the Southern Cross, Hydra, and Carina—that are visible only south of the equator. I joined Michael Turek, the photographer for this article, and a handful of other guests by a fire on the beach before dinner, and together we listened to De Figueiredo’s stories. Having been driven out of the country of his birth as a teenager, he had longed to return. Twenty-four years later, in the thick of a midlife crisis, he came back to southern Africa, eventually training to be a pilot.

There were rumours of trouble up north again, which had caused one of andBeyond’s resorts, near Vamizi, to shutter. When I asked De Figueiredo about it, he said, “It’s about money.” The discovery of rubies, gold, and natural gas was menacing Mozambique’s hard-won peace, but here on the beach, in a country twice the size of California, the danger felt abstract, and far away.

In Mozambique, I rediscovered my love of the sea. On the morning I met Tessa Hempson, principal scientist and programme manager at the conservation organisation Oceans Without Borders, I was still brimming with excitement after my first dive in 15 years. Having remastered the magical arts of equalising, breathing, and achieving neutral buoyancy, I drifted over the seafloor, gazing first at the coiled cerebral matter of brain coral, then at orange harlequin fish darting in and out of stubby-fingered digitate coral. Leathery sea anemones, with their many tendrils, fanned beneath me, revealing their brilliant purple interiors.

Farther along, chocolate dip damselfish were having a different sort of party, one with a strictly monochrome dress code. They flitted about in white tie and tails, up and over the gnarled basin of a plate coral, adhering to the rules of their fraternity. To be a scuba diver is to be the worst kind of gate-crasher—ill-attired, intrusive, full of a sense of entitlement.

The sea creatures are icy in their disdain. Even to ask you to leave is to deign to notice you, and draw attention to your bad manners, which they stoutly refuse to do.

Hempson, who describes herself as a “bush kid,” having grown up surrounded by wildlife in an area between Johannesburg and Maputo, told me she had spent the morning rolling hammerhead sharks onto their backs. I had heard that turning the creatures over lulled them into docility, but thought it was an urban legend. Hempson confirmed that it was true. “What is that called?” I asked her. “A tonic state,” she said easily, “like gin and tonic.” Once she has the sharks purring away happily under her, she installs telemetric devices in their bellies.

Tracking apex predators, along with monitoring beach erosion and recording soundscapes of the sea to catch everything from anthropogenic noise to whale song, is part of a day’s fieldwork for Hempson. The more difficult aspect of her job is to instill her love of the sea among those she describes as “stakeholders.” These include the local communities, for whom fish and other sea creatures are at times the only source of edible protein, but also the kind of rich, influential people who can afford to vacation at the resorts on Benguerra. (The archipelago has recently been declared a “hope spot”—one of a handful of “special places that are critical to the health of the ocean”—by Mission Blue, the conservation movement led by legendary American oceanographer Sylvia Earle.)

For Hempson, a lodge like andBeyond plays a critical role. On a human level, she explained, the resort has been a pioneer on the island. It helped build the school, the clinic, the church, and the community center. Its Hippo Water Rollers—plastic containers with handles—have made clean water easy to get and transport. The company provides skills training and engages the community in conservation work and education.

On the environmental front, andBeyond, with its long lease in the archipelago, serves not merely as a jumping-off point for Hempson’s fieldwork. It also has the potential to stimulate impact-driven luxury travel, which in turn could influence policy at the highest levels. “To change behavior,” she told me, “you have to reach people on an emotional level.” Hempson’s work, which she does in tandem with the Africa Foundation, embodies what the United Nations terms “intersectoral collaboration”—which is in turn crucial, the UN says, to the achievement of its sustainable-development goals.

When I told Hempson I had seen a dugong that morning after my dive, its smooth, bowed body catching the sun, its whiskered snout sniffing this way and that, she nearly fell out of her chair. “That’s unbelievable,” she said. “It’s hard to explain to people how precious that is.” Before coming to Bazaruto, Hempson said, she had only ever seen three dugongs. They were considered practically extinct until some 50 of the creatures showed up in the archipelago. “We had not thought there were so many left on the whole African coast, let alone in one area.”

Kisawa! The word had acquired a kind of mystery and glamour long before I stepped through the doors of the dazzling new resort of the same name on the southern tip of Benguerra Island. At andBeyond’s Dhow Bar, the name had been uttered with an awe-inflected hush. A Bulgarian lawyer spoke reverently of its vast 149-square-metre villas, swiftly dismissing the need for digs so grand. A South African builder, in between beers and talk of Bitcoin, looked at his wife and said, alluding to its INR 4,12,693-a-night price tag, “We can’t afford it, baby. We’re working-class!” The fabled status of Kisawa—the word means “unbreakable” in Tswa, the island language—was such that when I was picked up at andBeyond, it felt as if I were being transferred to the Ritz.

In the meantime the island of Benguerra had grown every day more magical, like Caliban’s isle, “full of noises, sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight, and hurt not.” I was taken to Kisawa by the bandanna-ed Q (short for Querino) Lucas Huo, who works as the marine, activities, and community liaison manager at Kisawa. Along the way, he stopped to point out herds of sunis, antelopes no bigger than whippets, that picked their way through the shrubbery and glanced coyly in our direction. We passed trees heavy with macuacuaand massala (monkey orange), from which the islanders make a kind of beer. Q made me taste the fruit. It was like an Asian mangosteen, pitted and wonderfully tart.

A low, bruised sky had hung over us all morning; just as Kisawa’s villas appeared, it began to rain. “A blessing,” Q said. The villas had long roofs of serried madjeka, framed by a sea that fell back for acres in enticing bands of blue.

If I was to describe Kisawa in the language of tourism—or indeed, in the language of my fellow travellers at the Dhow Bar—I would talk of the butler it provides each bungalow, the private pools, the enfilade of rooms divided by great sliding doors dressed in a local matting called esteira. I would talk of the long, turmeric-coloured sofas and the furniture from every corner of Africa, the redwood and rattan chairs from Cameroon, the bulb-shaped baskets from Nigeria. I would talk of Joseph Moubayed, the cobalt-eyed chef, who marshals the different strands of his background—Lebanon, Senegal, and France—to create food of such lightness and subtlety that I was left guessing at the origin of its flavours. (Was that crab with matapa,a local stew made from boiling cassava leaves and mixing them with coconut milk? Or muhammara infused with tinziva, a native fruit, a cousin of tamarind, with a tangy juice? Wait: Did he just use monkey orange in the ceviche to give it that wrenching back-of-the-mouth sourness?) I could talk of all this, yet never capture the feeling I had every evening at Kisawa, leaving for the main terrace in my villa’s dedicated electric Moke, driving through winding roads with silvered views of the sea, the twinkling of other villas in the distance. Torchlit pathways led to restaurants blazing with light, where Moubayed was cooking up fish pastels and curried lamb shank.

In the terrazzo-floored bar, with its porthole windows and beamed ceilings, a recording of André Marie Tala, that musical genius from Cameroon, was playing, evoking a heartbreaking optimism I have always associated with the early days of independence in the postcolonial world. It is a music that contains the promise of new beginnings, when hopes of self-reliance and autonomy were yet to be dashed by sectarian violence and civil war.

To ask a new hotel to capture the mood of the past is like asking a new house to feel lived-in. But that is exactly what Kisawa does, and it goes to the heart of the effortless chic the place exudes. Kisawa was started by a fixture of London society: Nina Flohr, the VistaJet heiress who is now also the Princess of Greece and Denmark, having recently married the youngest son of King Constantine. Flohr’s hands-on involvement in Kisawa is visible around the resort, from Moubayed’s dazzling menus, which they crafted together, to decorative touches like the record player and handpicked vinyl collection I found in my room.

Flohr also oversees the Bazaruto Center for Scientific Studies, the marine research center Kisawa founded and continues to fund. “Nina seeded it, and pushed it,” said Mario Lebrato, station manager and chief scientist at the BCSS. He described the archipelago as a marine “crossroads,” adding, “This is a super hot spot for migratory animals.” The BCSS supports conservation through the gathering of data, Lebrato explained, which it makes available to everybody, from Mozambique’s Ministry of the Sea to local universities, students, and researchers. “We treat it as research,” Lebrato said, holding a hydrophone he had been using to record ocean soundscapes, “but that has a conservation value.”

There were certain moments at Kisawa that I already look back on as among the happiest of my life. Perhaps it was the time I had just finished a long dive, in which I had seen blacktip reef sharks circling like a menacing shadow above the coral, sending a chill over the seafloor. Loggerhead turtles, with piebald faces, swam up into raking shafts of plankton-filled light. Afterward, in a bathroom the size of my apartment, with high-backed ebony chairs from Tanzania and a bathtub that looked like a dinosaur egg cracked open, the room was filled with a diffuse marine light. Beyond were dunes draped in purple beach morning glory. I was alone, by the sea. This was not luxury I had to think myself into. It emanated from the place itself, and I felt it in every fibre of my being.

Mozambique is the only country to have a modern weapon on its flag. The sight of that AK-47 framed against a yellow star on a red background, outside a government office in Vilankulo, was a reminder of the terrible violence its people have endured. On my first full day in Mozambique, I had talked to Isac Paulo Nhamirre, a muscular man with the leashed demeanour of a soldier. He described himself as working as a liaison between hotels and resorts, the local community, and the government. He could remember as if it were yesterday how he had been on his lunch break, aged 18, in school—it was 2:25 p.m.—when recruiters from the government arrived and forced him to join the army.

“You stand up, you stand up, you follow us,” they said. He remembers them giving him documents to sign. They made a stop at his house to tell his parents that he was joining up. “That I was not going back,” he said. “That this beautiful moment”—he was only in eighth grade, because the war had forced him to start school very late—“was over.” Nhamirre, now 37, went on to serve in Burundi. “It wasn’t a good place to be,” he said, recalling a world where child soldiers aged 12 and 13 had been brainwashed to kill without thinking. “It was horrible.”

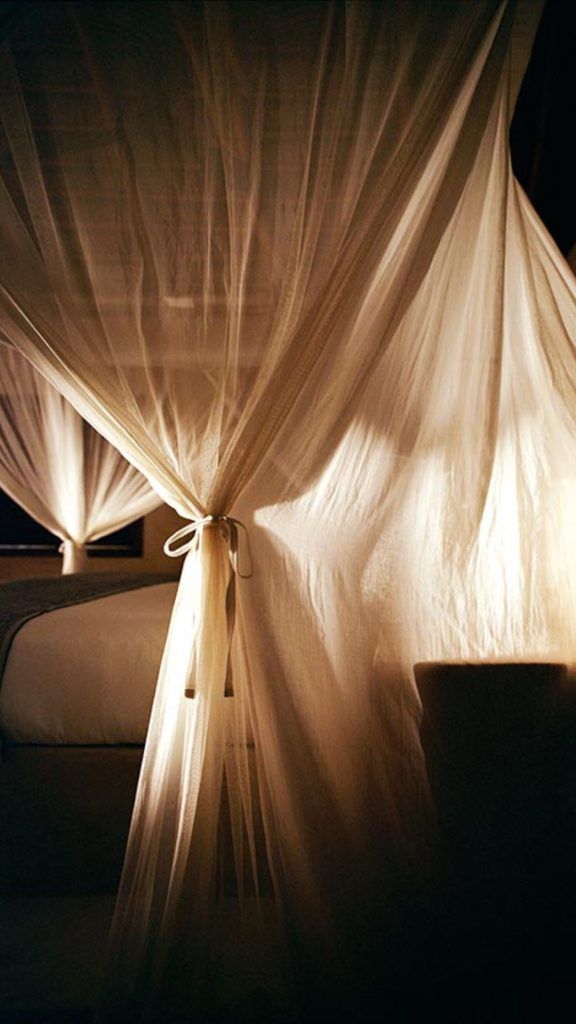

At Sussurro, a boutique hotel on the mainland overlooking Govuro lagoon, some 89 kilometres north of Vilankulo, I spent the morning of my last full day in Mozambique talking to men who had lived through the war. Sussurro is a place of spartan beauty—no Wi-Fi, no air-conditioning—a place of mosquito nets and long afternoons spent reading. I had asked Nick Taylor, the hotel’s Zimbabwean manager, to help arrange a conversation with veterans of the war, in part out of a need, amid all this arresting natural beauty, not to lose sight of the lived experience of those around me. It was only when Taylor, perhaps surprised by my request, asked me what I was writing about that I first said the word aloud. “Fragility.”

I realised that it was what I had felt all this while. The fragility of peace, both in Mozambique and now in the world at large, which the war in Ukraine had taught us to appreciate anew. But there was also environmental fragility, that delicate balance in the sea that people like Hempson and Lebrato were fighting so hard to preserve. None of this would have been apparent to me had another kind of fragility, related to our way of life, not been shattered by the pandemic. We had thought the momentum of our modern lives was unstoppable. But it had proved more fragile than we could ever have imagined.

The tide had retreated. In that gap between ebb and flow, there is a window of time in which it is possible to drive along the beach from Sussurro to Vilankulo airport. We were soon racing over the wet sand in a blue Mazda pickup truck. The sea was on my left, an embankment of red earth on my right, dotted with frayed palms, fishing nets, and the wreckage of washed-up boats.

The sea reminds us of our mammalian need to breathe. The dugong can stay underwater for a time, but what makes it like us on the most primal level, separating it from the creatures of cold blood and scales, is that it must eventually come up for air. This week in Mozambique, too, had in literal and metaphorical ways been a kind of surfacing. It had restored to me my sense of curiosity and wonder. An old restlessness and joy had returned, reminding me of why one ventured out into the world at all. Sloughing off the fears the pandemic had engendered, it had taught me what it was to breathe again.

The Keys to Coastal Mozambique by Samantha Falewée

Getting to Mozambique

Lufthansa, Singapore Airlines, and Air India operate various connecting flights to Vilankulos from major Indian cities such as New Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, and Kolkata.

Where to stay

andBeyond Benguerra Island

Inside Bazaruto Archipelago National Park, honeymoon-perfect villas await—but the real draws are the wildlife experts, scuba-diving excursions, and sailing on a dhow. Doubles from INR 1,37,852, all-inclusive

Kisawa

This resort on Benguerra Island has an award-winning design: the accommodations were built using sustainable materials like woven native grasses. Each bungalow sits on its own private acre, has its own pool, and comes with a butler. Doubles from INR 4,17,683, all-inclusive

Sussurro

This boutique property, which opened in 2021 on the mainland’s Nhamabue Peninsula, is supported by renewable energy and local fishing and farming. Doubles from INR 94,928, all-inclusive.

Related: Here’s An Adventure Trail Across Mozambique That Lead To Its Hidden Treasures!